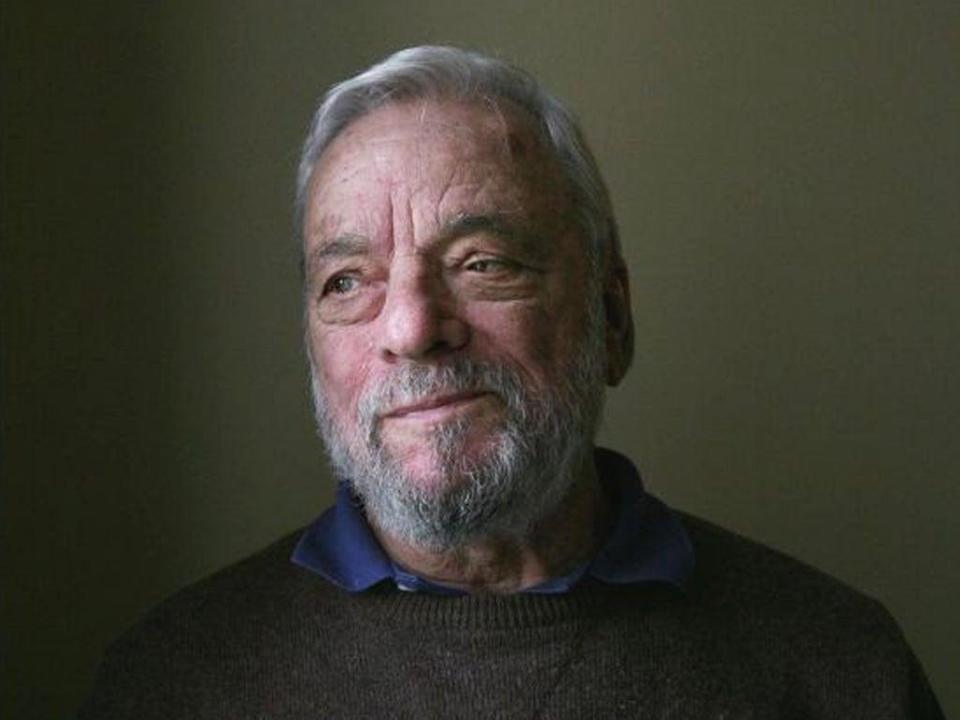

Stephen Sondheim, the songwriter who reshaped the American musical theater in the second half of the 20th century with his intelligent

Sondheim’s death was announced by Rick Miramontez, president of DKC/O&M. Sondheim’s Texas-based attorney, Rick Pappas, told The New York Times the composer died Friday at his home in Roxbury, Connecticut.

Sondheim influenced several generations of theater songwriters, particularly with such landmark musicals as “Company,” “Follies” and “Sweeney Todd,” which are considered among his best work. His most famous ballad, “Send in the Clowns,” has been recorded hundreds of times, including by Frank Sinatra and Judy Collins.

The artist refused to repeat himself, finding inspiration for his shows in such diverse subjects as an Ingmar Bergman movie (“A Little Night Music”), the opening of Japan to the West (“Pacific Overtures”), French painter Georges Seurat (“Sunday in the Park With George”), Grimm’s fairy tales (“Into the Woods”) and even the killers of American presidents (“Assassins”), among others.

Tributes quickly flooded social media as performers and writers alike saluted a giant of the theater. “We shall be singing your songs forever,” wrote Lea Salonga. Aaron Tveit wrote: “We are so lucky to have what you’ve given the world.”

“The theater has lost one of its greatest geniuses and the world has lost one of its greatest and most original writers. Sadly, there is now a giant in the sky,” producer Cameron Mackintosh wrote in tribute. Music supervisor, arranger and orchestrator Alex Lacamoire tweeted: “For those of us who love new musical theater: we live in a world that Sondheim built.”

For those of us who love new musical theater: we live in a world that Sondheim built.

My spirit is low, and I swear the city is quieter than usual tonight with the knowledge that he’s gone.

Feeling thankful for all he created and for the awe he will continue to inspire.

❤️💔❤️— Alex Lacamoire (@LacketyLac) November 26, 2021

Six of Sondheim’s musicals won Tony Awards for best score, and he also received a Pulitzer Prize (“Sunday in the Park”), an Academy Award (for the song “Sooner or Later” from the film “Dick Tracy”), five Olivier Awards and the Presidential Medal of Honor. In 2008, he received a Tony Award for lifetime achievement.

Sondheim’s music and lyrics gave his shows a dark, dramatic edge, whereas before him, the dominant tone of musicals was frothy and comic. He was sometimes criticized as a composer of unhummable songs, a badge that didn’t bother Sondheim. Frank Sinatra, who had a hit with Sondheim’s “Send in the Clowns,” once complained: “He could make me a lot happier if he’d write more songs for saloon singers like me.”

To theater fans, Sondheim’s sophistication and brilliance made him an icon. A Broadway theater was named after him. A New York magazine cover asked “Is Sondheim God?” The Guardian newspaper once offered this question: “Is Stephen Sondheim the Shakespeare of musical theatre?”

A supreme wordsmith — and an avid player of word games — Sondheim’s joy of language shone through. “The opposite of left is right/The opposite of right is wrong/So anyone who’s left is wrong, right?” he wrote in “Anyone Can Whistle.” In “Company,” he penned the lines: “Good things get better/Bad gets worse/Wait — I think I meant that in reverse.”

He offered the three principles necessary for a songwriter in his first volume of collected lyrics — Content Dictates Form, Less Is More, and God Is in the Details. All these truisms, he wrote, were “in the service of Clarity, without which nothing else matters.” Together they led to stunning lines like: “It’s a very short road from the pinch and the punch to the paunch and the pouch and the pension.”

“As a writer, I think what I am is an actor. I write conversational songs, so the actors find that the rise and fall of the tune, the harmonies, the rhythms, help them as singers to ACT the song. They don’t have to act against it.” -Stephen Sondheim pic.twitter.com/zQlN7gKfSh

— Ava DuVernay (@ava) November 27, 2021

Taught by no less a genius than Oscar Hammerstein, Sondheim pushed the musical into a darker, richer and more intellectual place. “If you think of a theater lyric as a short story, as I do, then every line has the weight of a paragraph,” he wrote in his 2010 book, “Finishing the Hat,” the first volume of his collection of lyrics and comments.

Early in his career, Sondheim wrote the lyrics for two shows considered to be classics of the American stage, “West Side Story” (1957) and “Gypsy” (1959). “West Side Story,” with music by Leonard Bernstein, transplanted Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” to the streets and gangs of modern-day New York. “Gypsy,” with music by Jule Styne, told the backstage story of the ultimate stage mother and the daughter who grew up to be Gypsy Rose Lee.

It was not until 1962 that Sondheim wrote both music and lyrics for a Broadway show, and it turned out to be a smash — the bawdy “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” starring Zero Mostel as a wily slave in ancient Rome yearning to be free.

Yet his next show, “Anyone Can Whistle” (1964), flopped, running only nine performances but achieving cult status after its cast recording was released. Sondheim’s 1965 lyric collaboration with composer Richard Rodgers — “Do I Hear a Waltz?” — also turned out to be problematic. The musical, based on the play “The Time of the Cuckoo,” ran for six months but was an unhappy experience for both men, who did not get along.

It was “Company,” which opened on Broadway in April 1970, that cemented Sondheim’s reputation. The episodic adventures of a bachelor (played by Dean Jones) with an inability to commit to a relationship was hailed as capturing the obsessive nature of striving, self-centered New Yorkers. The show, produced and directed by Hal Prince, won Sondheim his first Tony for best score. “The Ladies Who Lunch” became a standard for Elaine Stritch.

The following year, Sondheim wrote the score for “Follies,” a look at the shattered hopes and disappointed dreams of women who had appeared in lavish Ziegfeld-style revues. The music and lyrics paid homage to great composers of the past such as Jerome Kern, Cole Porter and the Gershwins.

In 1973, “A Little Night Music,” starring Glynis Johns and Len Cariou, opened. Based on Bergman’s “Smiles of a Summer Night,” this rueful romance of middle-age lovers contains the song “Send in the Clowns,” which gained popularity outside the show. A revival in 2009 starred Angela Lansbury and Catherine Zeta-Jones was nominated for a best revival Tony.

“Pacific Overtures,” with a book by John Weidman, followed in 1976. The musical, also produced and directed by Prince, was not a financial success, but it demonstrated Sondheim’s commitment to offbeat material, filtering its tale of the westernization of Japan through a hybrid American-Kabuki style.

In 1979, Sondheim and Prince collaborated on what many believe to be Sondheim’s masterpiece, the bloody yet often darkly funny “Sweeney Todd.” An ambitious work, it starred Cariou in the title role as a murderous barber whose customers end up in meat pies baked by Todd’s willing accomplice, played by Angela Lansbury.

The Sondheim-Prince partnership collapsed two years later, after “Merrily We Roll Along,” a musical that traced a friendship backward from its characters’ compromised middle age to their idealistic youth. The show, based on a play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, only ran two weeks on Broadway. But again, as with “Anyone Can Whistle,” its original cast recording helped “Merrily We Roll Along” to become a favorite among musical-theater buffs.

“Sunday in the Park,” written with James Lapine, may be Sondheim’s most personal show. A tale of uncompromising artistic creation, it told the story of artist Georges Seurat, played by Mandy Patinkin. The painter submerges everything in his life, including his relationship with his model (Bernadette Peters), for his art.) It was most recently revived on Broadway in 2017 with Jake Gyllenhaal.)

Three years after “Sunday” debuted, Sondheim collaborated again with Lapine, this time on the fairy-tale musical “Into the Woods.” The show starred Peters as a glamorous witch and dealt primarily with the turbulent relationships between parents and children, using such famous fairy-tale characters as Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood and Rapunzel. It was most recently revived in the summer of 2012 in Central Park by The Public Theater.

“Assassins” opened off-Broadway in 1991 and it looked at the men and women who wanted to kill presidents, from John Wilkes Booth to John Hinckley. The show received mostly negative reviews in its original incarnation, but many of those critics reversed themselves 13 years later when the show was done on Broadway and won a Tony for best musical revival.

“Passion” was another severe look at obsession, this time a desperate woman, played by Donna Murphy, in love with a handsome soldier. Despite winning the best-musical Tony in 1994, the show barely managed a six-month run.

A new version of “The Frogs,” with additional songs by Sondheim and a revised book by Nathan Lane (who also starred in the production), played Lincoln Center during the summer of 2004. The show, based on the Aristophanes comedy, originally had been done 20 years earlier in the Yale University swimming pool.

One of his more troubled shows was “Road Show,” which reunited Sondheim and Weidman and spent years being worked on. This tale of the Mizner brothers, whose get-rich schemes in the early part of the 20th century finally made it to the Public Theater in 2008 after going through several different titles, directors and casts.

He had been working on a new musical with “Venus in Fur” playwright David Ives, who called his collaborator a genius. “Not only are his musicals brilliant, but I can’t think of another theater person who has so chronicled a whole age so eloquently,” Ives said in 2013. “He is the spirit of the age in a certain way.”

Sondheim was born March 22, 1930, into a wealthy family, the only son of dress manufacturer Herbert Sondheim and Helen Fox Sondheim. At 10, his parents divorced and Sondheim’s mother bought a house in Doylestown, Pa., where one of their Bucks County neighbors was lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II, whose son, James, was Sondheim’s roommate at boarding school. It was Oscar Hammerstein who became the young man’s professional mentor and a good friend.

He had a solitary childhood, one that involved verbal abuse from his chilly mother. He received a letter in his 40s from her telling him that she regretted giving birth to him. He continued to support her financially and to see her occasionally but didn’t attend her funeral.

Sondheim attended Williams College in Massachusetts, where he majored in music. After graduation, he received a two-year fellowship to study with avant-garde composer Milton Babbitt.

One of Sondheim’s first jobs was writing scripts for the television show “Topper,” which ran for two years (1953-1955). At the same time, Sondheim wrote his first musical, “Saturday Night,” the story of a group of young people in Brooklyn in 1920s. It was to have opened on Broadway in 1955, but its producer died just as the musical was about to go into production, and the show was scrapped. “Saturday Night” finally arrived in New York in 1997 in a small, off-Broadway production.

Sondheim wrote infrequently for the movies. He collaborated with actor Anthony Perkins on the script for the 1973 murder mystery “The Last of Sheila,” and besides his work on “Dick Tracy” (1990), wrote scores for such movies as Alain Resnais’ “Stavisky” (1974) and Warren Beatty’s “Reds” (1981).

Over the years, there have been many Broadway revivals of Sondheim shows, especially “Gypsy,” which had reincarnations starring Angela Lansbury (1974), Tyne Daly (1989) and Peters (2003). But there also were productions of “A Funny Thing,” one with Phil Silvers in 1972 and another starring Nathan Lane in 1996; “Into the Woods” with Vanessa Williams in 2002; and even of Sondheim’s less successful shows such as “Assassins” and “Pacific Overtures,” both in 2004. “Sweeney Todd” has been produced in opera houses around the world. A reimagined “West Side Story” opened on Broadway in 2020 and this year an off-Broadway “Assassins” opened off-Broadway at Classic Stage Company and a scrambled “Company” opened on Broadway with the gender of the protagonist switched. A film version of “West Side Story” is to open this December directed by Steven Spielberg.

Sondheim’s songs have been used extensively in revues, the best-known being “Side by Side by Sondheim” (1976) on Broadway and “Putting It Together,” off-Broadway with Julie Andrews in 1992 and on Broadway with Carol Burnett in 1999. The New York Philharmonic put on a star-studded “Company” in 2011 with Neil Patrick Harris and Stephen Colbert. Tunes from his musicals have lately popped up everywhere from “Marriage Story” to “The Morning Show.”

An HBO documentary directed by Lapine, “Six by Sondheim,” aired in 2013 and revealed that he liked to compose lying down and sometimes enjoyed a cocktail to loosen up as he wrote. He even revealed that he really only fell in love after reaching 60, first with the dramatist Peter Jones and then in his last years with Jeff Romley.

“Every so often someone comes along that fundamentally shifts an entire art form. Stephen Sondheim was one of those. As millions mourn his passing I also want to express my gratitude for all he has given to me and so many more,” singer and actor Hugh Jackman wrote via Twitter.

AP